A Lesson to Learn

Image by Vitolda Klein from Unsplash

Childhood Grief. A big topic. One that was neglected in the past, but has been explored by researchers, therapists and parents in recent decades. A topic that, by definition, can only really be experienced by children. Children who, depending on their age, development, and environment, may or may not have the skills to fully share with clarity what they face and how they feel. And, just to make things even more complex – each person who grieves, does so differently, including children.

I can write about my experiences in grief and loss – but I can only do so as an adult. As a young child I experienced the loss of pets – dogs, goldfish, etc. As a teenager my grandfather and one of my aunts died, and then in my 20s, some more elderly relatives passed away. But my most impactful experiences of loss and grief have been in my 30s and 40s. Which is when most people might start to lose loved ones in their lives.

When a child grieves, we might assume they are saddened, confused, and maybe overwhelmed by the loss. But what I know is – they are watching. They are watching us, listening to us, and learning from what the adults in the room are doing. How the adults are feeling, how things are different from before.

I wasn’t invited to listen to conversations or ask questions about my extended family members who died when I was young. I was never taught at school about death, dying or grief. But I do remember seeing my mum cry for the first time on the way to her sister’s funeral. I do remember overhearing an adult say “another one bites the dust” at the funeral of an elderly person I didn’t even know. I do remember repeating this phrase and being shamed for being so insensitive. But most of my memories are no longer clear simply due to the passing of time. Therefore, I can’t really speak to the topic of childhood grief from my personal perspective. So instead I will walk us through my observations and the experiences of my son, Cameron.

I am a mum to beautiful twin boys. One of those beautiful boys – Thomas, died of brain cancer eleven days before his 8th birthday. Their 8th birthday. As a result, the other of those beautiful boys – Cameron, became a bereaved sibling.

We arrived at Hummingbird House the day before Thomas died. This was the children’s hospice that provided us with such wonderful end-of-life and after-life care. Family was all around as Thomas slept for most of the day as we talked to him, held him and witnessed his final hours together. Cam was a young boy looking around with big eyes; standing in a room full of sad adults who were gathered around his brother, Tom. We had explained what was happening. Cam knew his brother was going to die. I could see how much he wanted to help. How much he wanted to make us smile instead of cry. Just like during the traumas of treatment, Tom was the focus that day and Cam was watching on.

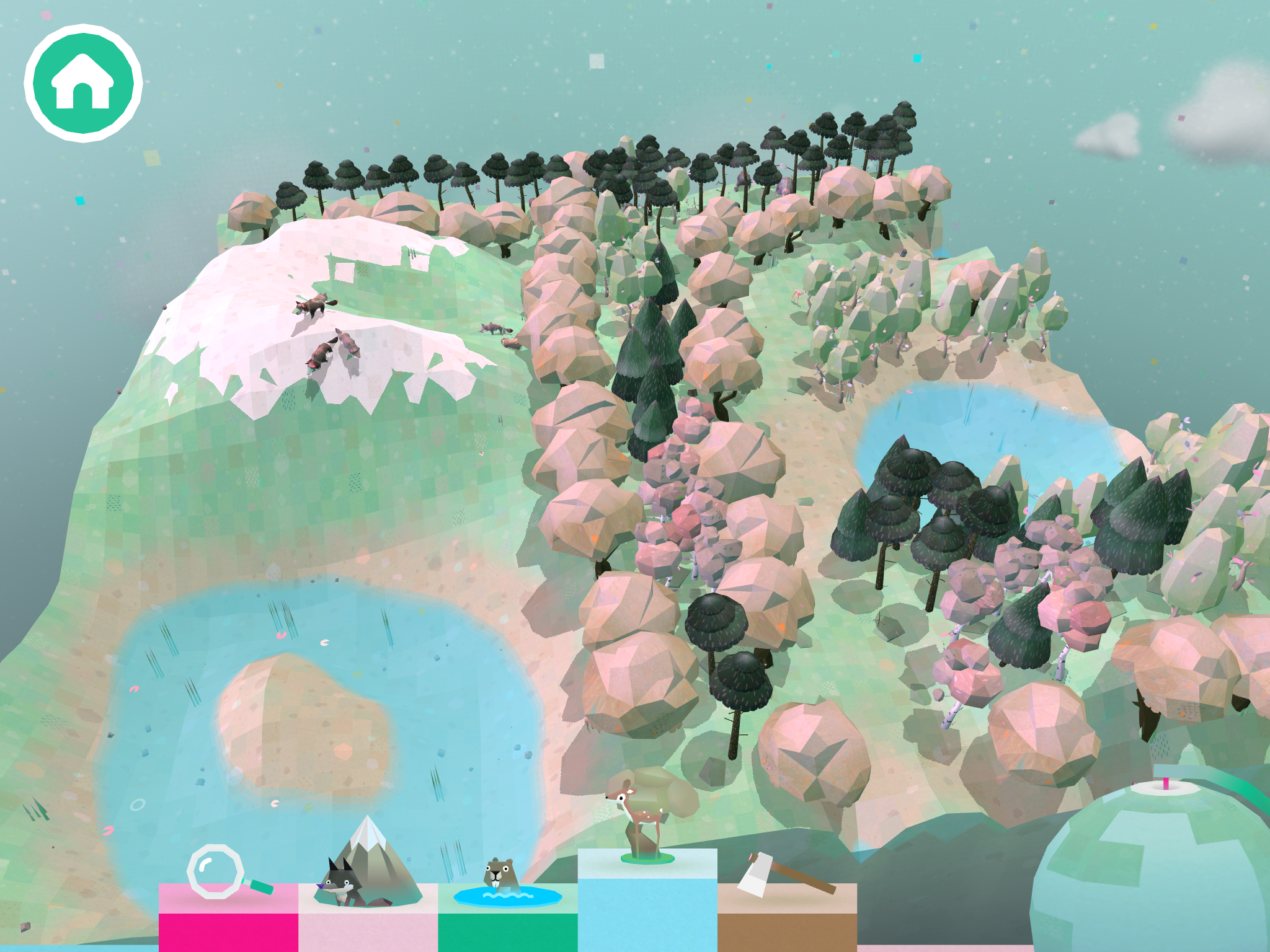

Without much parental direction, he came and went out of the room – playing outside, helping the staff with little jobs and chatting away in the office. Always returning to the same scene in that room. He would come and ask a question or two but still seemed unsure of how to help. Only able to watch. Then Cam settled in with Tom’s hospital Ipad to play one of the games – Toca Nature. A game that allows the player to create landscapes with trees, rivers, mountains and animals, and to explore different environments. And then he had an idea. Cam started to transform these landscapes into letter designs – ‘T’ for Thomas, ‘C’ for Cameron. He would proudly show us and say,

“I made this for you. I made this for Tom.”

He made more and more. I remember smiling at him, marvelling at how thoughtful he was, and how proud I was. And off he would go to create the next new masterpiece.

With Tom’s death, I remember wanting to protect Cam from the pain. The pain I was feeling was crushing and so I imagined the same for him. I wanted to know every sorrowful thought that crossed his mind and to know how much this loss was impacting his life. After a year of caregiving with great focus on my sick chick, ‘Mother Hen’ had developed as my main identity. I had become used to comforting Thomas in his suffering and was desperate to shift my comfort to Cam. I was ready with a psychologist appointment, a support plan to take to his teacher and I even took a course about supporting bereaved siblings.

But… Cam didn’t cry. He didn’t shut down. Not in the days that followed, not at Tom’s funeral, not even once he was back at school. I expected a bigger display, and I was worried when it didn’t come. But Cam didn’t seem to need my help and I didn’t know what to do with that.

Cam asked some questions now and then, as you would expect from an eight-year-old boy. Questions like, “Was it my fault?” or “Would it have been better if it had been me that died instead?” Questions asked quite matter-of-factly but answered with passion and fire. “NO! One hundred times no my Sweetpea! None of this is your fault and in no way would things have been better for you to be gone instead. My pain would be just as great if I had lost you.”

Really, what I saw the most … was that he was lonely for his brother. For the other kid in the house that had always been there. A friend to share a bedroom with, to eat dinner with. To cuddle mum together, to play and giggle together and to zombie out on the couch watching cartoons together. The oppressive quiet that our house now held was deafening for me and for this lonely little boy.

As the months went on, Cam witnessed my grief - which was far more explicit. Mum - gazing off into space. Mum - randomly crying at any time of day or night. Mum - handling his brother’s photos, toys, and clothes with reverence and despair all at once. Mum - unafraid to keep Tom in conversations and celebrations. Over time he watched me develop remembrance rituals and throw myself into legacy projects and causes. Raising awareness and funds to fight the demon that took his brother.

Cam also saw how the school kids responded to finding out Thomas had died. The school my boys attended decided that they wouldn’t talk with the other students about Tom’s death. They believed the students didn’t need that conversation; they were too young. Whatever the reason, they made the choice to avoid the big sad elephant in the room. I disagreed and was so anxious about how it would all play out.

With no adults to set the tone and provide some guidance, it left the kids to go looking for answers elsewhere. And so, they went to my son. Every day, more questions from more and more classmates. “How did Thomas die? Why did he die? Why aren’t you crying?”

Questions posed to this eight-year-old boy who had helped carry his brother’s coffin from a big, crowded room just two weeks before. Curiosity is understandable but kids can also be cruel when they see difference or when they don’t understand. It was surprising to me that the research shows that bereaved children can often become victims of bullying*. Taunts like “Your brother died” – just to see what response they could get. “I wish you had died instead of Tom”. Comments which I am sure provoked Cam’s lurking thoughts that maybe it should have been him. Horrendous and unfair taunts that I couldn’t protect him from.

Graduation Day at the end of Year 6 saw us arriving at the school hall for the ceremony and I was doing my very best to hold it together. Cam was walking next to me and holding my hand. He looked up at me and told me I shouldn’t cry. I said to him “There will definitely be tears mate. I am proud of you, and I am sad that Tom isn’t here.” He thought for a minute and responded by saying:

“Well, you can cry then. The tears from your left eye can be sad and the tears from your right eye can be for joy.” Tears flooded both cheeks that night.

When he finally moved into high school with new staff, new students and new friends, this was his opportunity to not be known as that boy with a dead twin brother. A chance for Cam to start with a fresh identity that he could shape and fully own in this new community, separate to the tragedy that was part of his family history. And he did. Cam thrived and gathered a lovely group of mates like he hadn’t had before. He also had full control of if, when, and how he would tell his new group of friends about Thomas. I’m not sure what led up to that day, but he did so within about eight months. I’ve watched him speak freely about Tom, their history, funny stories about growing up together with these boys. He feels no shame or stigma in this sharing of his twin brother. As far as I know, his friends have been kind and have only shown curiosity without judgement or mockery.

I wrote a book about Tom’s journey and for a long time I couldn’t allow Cam to read it. We had shielded Cam from so much of what Tom was going through and I wanted him to be old enough to understand and manage his emotions around the story. ‘Big Hand, Little Hand’ was published just as Cam turned nine years old, less than a year after Tom’s death. Cam pressured me for years to read it. This ramped up particularly once he hit high school. I was so nervous about the timing and lots of people weighed in on whether I should allow it. Eventually this worry manifested as wanting to control his experience. When he was 13, I said yes but only if we could read it together. And only if we could spread out the timing of when we would read it – one chapter at a time. I wanted us to talk about it, and he might want to ask me questions. I was back there, wanting to witness and manage his grief. I wanted control and so he lost interest after the first chapter. “Why can’t I just read it by myself?”

It is not fair of me to control Cam’s experience and emotions around his loss and that time of our lives – not anymore. He is not a little boy anymore. Cam has shown amazing emotional maturity and intelligence over the past six years. I know this, yet here I was – still flooded with the guilt of not being able to protect Tom and so I was over-compensating with Cam. I have tried so hard not to flap and hover over him and mostly, I believe I do a good job. I try to allow him the freedom of youth, some autonomy and independence where I can. I try to give him the mum I was always meant to be.

But I am not just ‘a mum’ now, I am also a bereaved mum and my worry is entrenched.

So, worried or not, with this awareness, I must purposefully step back. To know when I am reaching too much for the wheel. To trust him to be ok without my wings around him. The balancing act is fraught, and I am sure I make mistakes, but I will keep trying.

As parents of bereaved siblings, I think it is important to show our kids what grief can look like. There is no point in hiding away our sorrow, it is a normal and human response to loss and in its essence – grief is an expression of love. I want us to be open and comfortable with conversations, questions and emotional responses on every topic, including grief.

One of the concepts of grief that has really resonated with me is that of ‘Continuing Bonds’. That while my son has died and is no longer physically here with me, that I can still have a relationship with him. I keep his presence with me because he is still my son. I keep talking about him, because he is still my son. I never want Cam to forget his brother or be afraid to remember him. I want him to reminisce about his favourite times with his twin brother, to look at photos and videos fondly and to laugh or cry as he needs to.

The night Cam gave me permission to cry from both eyes as he graduated from primary school, I presented an award that was set up in Tom’s memory. Thomas was diagnosed as the boys finished Year 1 and so it was difficult to know which subject to attach to this award. I remember how much my boys loved to read. Every night, the boys would tuck under each of my arms at bedtime, and we would do our readers together. And so, Tom’s award was dedicated to the top English student in each graduating class. Every year, I am invited to present this award, and Tom is introduced to the crowd. Families that never knew Tom, but now they do. Even if just for a few minutes. Cam asked me last year a question that warmed my soul. “Can I present Tom’s award one day mum?” Now there’s a continuing bond for my boys – a young man carrying on a gesture of his brother’s legacy. A bittersweet joy – but joy all the same.

We try to prepare our kids for the big world that awaits – with its potential for achievement and connection and happiness. We don’t want scary stuff to happen to them. We want to protect them from the challenges, the rejections, the suffering. The scary stuff is inevitable though and so shouldn’t we also prepare our kids for the big hard stuff, like loss and grief? They are looking to us, they are watching us, they are learning from us.

As the adults in the room, we also have a lesson to learn. To find the middle ground, the balance between micro-managing their pain and avoiding the topic at all costs. To model and show them how to be honest in their emotions and find ways to continue the bonds they have with loved ones who have died.

Cam has been through more than most kids his age and with each struggle he continues to amaze me with his resilience and kind heart. We shouldn’t underestimate our children – bereaved or non-bereaved. We should simply offer them support, guidance, honesty and love with every life lesson they learn – even the big hard stuff like grief.

Written and published with permission of my son, Cameron.

* Cain, A. C., & LaFreniere, L. S. (2015). The Taunting of Parentally Bereaved Children: An Exploratory Study. Death Studies, 39(4), 219–225. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2014.975870